From its earliest days, the story of the Foundling Hospital includes glimpses into the lives of foundlings and mothers from black and minority ethnic backgrounds. The vision of founder, Thomas Coram, was that any healthy child should be admitted if there was a bed – ethnicity was not an issue, so it was only occasionally recorded.

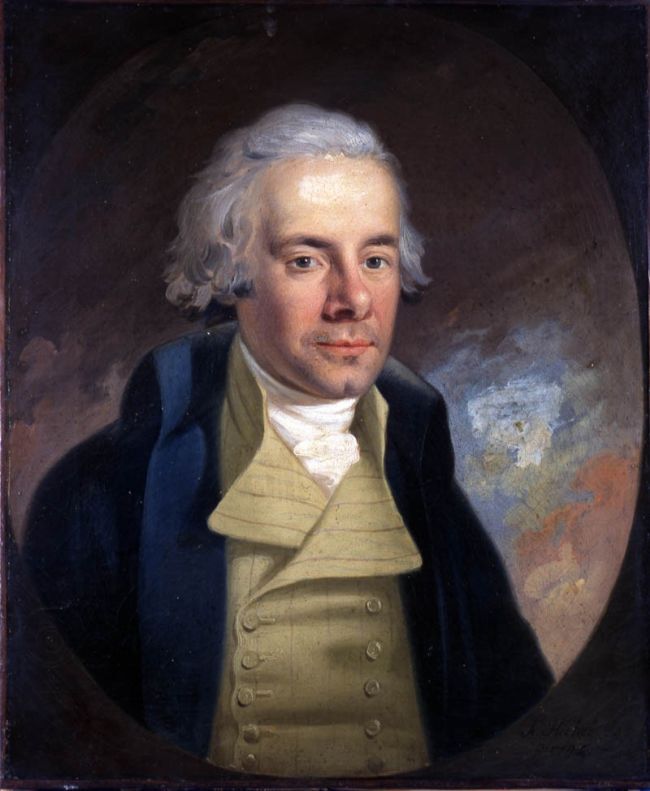

The Foundling Hospital’s history reflects changing attitudes in British society: the first generation of governors were inevitably wealthy as a result of the slave trade. Subsequent generations of governors include men who were prominent in the campaign to abolish it. Intriguingly, the records show that the Foundling Hospital received at least one generous donation from William Wilberforce, who led the abolition movement in Britain.

In her talk for Black History Month, Black Lives and the Early Years of the Foundling Hospital, Carol Harris looks at the foundlings and governors who are part of this extraordinary time in history.

Hakewill, Jamaica

Foundlings from black and minority ethnic backgrounds were part of the story of the Foundling Hospital from the very beginning. Our founder, Thomas Coram, said that every child that could be taken in would be given a home.

Ethnicity was not routinely recorded as it was not usually considered relevant. Words which would not be acceptable today such as ‘ tawny’, ‘negro’, and ‘mulatto’ occur occasionally in the records, usually as means of identifying the child should they be reclaimed by its parents.

July Green, Foundling no. 75, is one such rare example: he was admitted to the hospital in May 1741 and was described as being ‘of a very tawny complexion’.

Admission certificate for July Green, 1741

Another is Ann Watson, Foundling 17342, described as ‘a mulatto’. Admitted in 1778, she was reclaimed by her mother in November 1786. By that time, her mother had married William Green of Barbados. The records say that the family planned to go ‘with the black people to Sierra Leone’ as part of a scheme to create a new colony. The plan was promoted by the British government and the Committee for the Black Poor, a charity led by Jonas Hanway, who was also a vice-president of the Foundling Hospital.

Slavery – its profits and its abolition – was also part of the story of black history at the Foundling Hospital. In the eighteenth century, every part of the British economy was connected to the slave trade and so the merchants and aristocrats who founded the charity were all linked to it.

Coram Annual Report 1978-99

The Foundling Hospital’s history also reflects the changing times and attitudes towards the slave trade. One of several examples is the Thornton family, generations of whom were governors. Much of their fortune came from sugar imported from the Caribbean. John Thornton, a second-generation governor from 1787, was a good friend and relation of William Wilberforce, the leader in Britain of the movement to abolish slavery (pictured below).

Visit:

‘Tiny Traces: African and Asian Children at London’s Foundling Hospital’ exhibition at the Foundling Museum until 19 February 2023.

For further reading:

Black and British: a forgotten history by David Olusoga, pub. by PanMacmillan

Find out more about foundling Ann Watson on the Coram Story site.