The conference drew on Coram’s three centuries of expertise on elevating the life chances of society’s most vulnerable children. This history was foregrounded by John Caldicott, a former pupil at the Foundling Hospital, which cared for children who could not be raised by their birth families on Coram’s site until it closed in the 1950s. He spoke of the stigma of illegitimacy he experienced as a child and his desire to be talked to, listened to and loved, in the years before modern psychology had provided an evolved understanding of children’s emotional needs. His memories shocked the room, but the speakers showed that in 80 years time, we may be just as shocked by how children of today are marginalised.

Jenny Coles CBE, chair of What Works for Children’s Social Care and a Coram trustee, highlighted a number of achievements over the last two decades, but also the thorny issues that persist such as mental health, alcohol and drug misuse and violence and domestic abuse, poverty and exploitation. While there has been progress for many, there is still a cohort of children who are largely invisible in society. She urged a focus on the difference that schools and education can make beyond exam results. She also recognised the importance and strength of the family in enabling children to achieve their potential. While there can be a tension between the interest of the child and the family, this should be considered and embraced to achieve real change for children.

Dr Ann Hagel, research lead at the Association of Young People’s Health, highlighted that adolescent health often receives less attention but is a crucial time for establishing life patterns and further embedding health inequalities. While this is not new learning, Dr Hagel spoke of the chasm between the number of young people experiencing poor mental health and the number receiving services and the stark need for change. Unlike all other age groups, the biggest causes of death for adolescents are preventable.

Dr Timo Hannay, founder of SchoolDash, gave an insight to how we can better use data to drive service improvement. He showed that looking at data for large populations, such as regional data, only gave broad findings and instead thought about the greater insight – and ability to inform action – finer grained data analysis provides. He also called for the sector to move away from simply focusing on the metrics that we have data on and to focus study instead on the data that really matters most, including the home environment and well-being.

Andrew Carter, Director of Children’s Services at Lambeth, encouraged a move away from thinking about children and young people as a list of problems, and instead to give them their voice and recognise their strengths and vulnerabilities. While young people are often thought of as the problem and cause of crime, one in ten are instead the victims of crime. Services are designed by adults for children, or even for adults, not truly centred on what children want and need. In his role, he ensures services and professionals see children as children, both vulnerable and holding huge potential, not as problems to be solved.

Professor Sir Anthony Finkelstein, president of City University, called for the sector to be more demanding of technological solutions to improve outcomes for children in care. While the power of the computers doubles every 18 months, social care uses systems that were out of date 15 years ago. The rate of technological change is startling and this should be seen as an opportunity to forge wholesale change for the young people in our care.

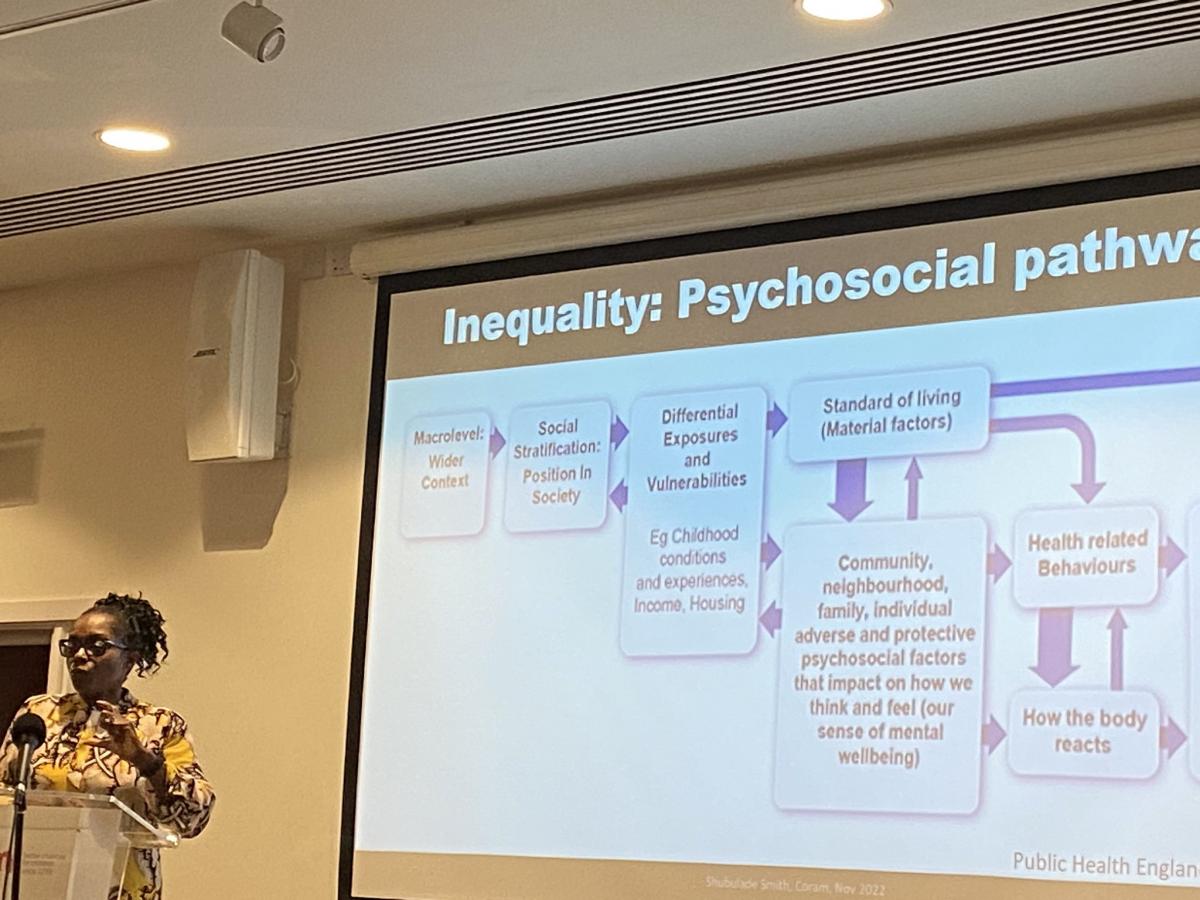

Dr Shubulade Smith CBE, consultant psychiatrist at the Maudsley Hospital, works with patients with multiple and complex mental health issues. The adults she works with are marginalised as adults and were marginalised as children. She showed that while the causes of mental health problems are well understood – genetics, biology, trauma, substance use, social isolation and poverty – not enough action is taken to intervene to change life courses. Childhood maltreatment is a key determinant of violence as an adult. Inconsistent parenting, acrimonious relationships between parents and ongoing discrimination act as recurrent traumas for children that leave psychological scars into adulthood. Dr Smith called for structures and institutions that help children achieve their potential to be strengthened, and for socio-economic factors to be addressed.

Professor Judith Rankin, Dean, Newcastle University discussed the importance of pregnancy and early years to make a difference for children throughout their childhood and beyond. The earliest investments bring the greatest returns, which is why the Marmot review placed such strong emphasis on the best start in life. She also highlighted just how stark the divide in outcomes between the north and south of the country is on both long term measures such as life expectancy, poverty, food security, but also recent measures such as learning loss during Covid compounding these inequalities. She urged the sector to consider the drivers of health inequalities – poverty, power, resources – and how change in a child’s first 1001 days can alter their life course. There are well documented problems with the quality of maternity care for ethnic minority families, which must be considered as part of the picture in inequalities for children given the importance of the perinatal period.

Dr Susie Bower-Brown, a lecturer in social psychology lecturer at UCL, discussed the increase in people identifying as gender diverse as awareness has grown and language has evolved. But despite this growing understanding, gender diverse young people are still one of the most marginalised groups, with around half of trans young people having attempted suicide. Her research found discrimination on many levels – from peers, teachers and wider society. She called on schools and all services and society to assume, accept and celebrate gender diversity, realising the opportunity this brings to improvements for all children, not only gender diverse children.

The conference featured a wide range of cross-sector and multi-professional expertise and experience, but key themes to emerge centred around the failure to improve life chances for the invisible, marginalised children. Significant progress has been made, but repeated failures exist. Past experience predicts the future, with unequal access to support and resurgent gaps meaning that both advantage and disadvantage are compounded as children grow into adults. In bringing together the range of expertise across the sector, Coram aims to highlight the opportunities that exist from technology, evidence, data and social to push for lasting change for children.